It has been a long time since I wrote my last post. To be honest, I have been quite lazy since Tet holiday and lacked the motivation to complete personal tasks. I’m still in my own head a lot 😂.

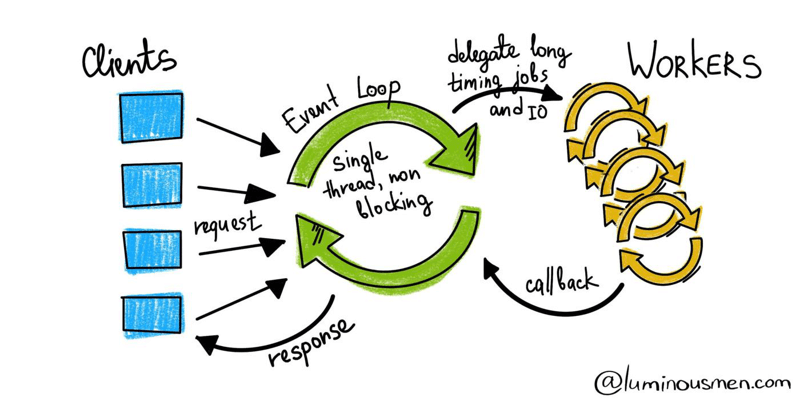

Fortunately, I have made up my mind to continue learning and sharing, and the topic today is Asynchronous Programming in Python. This topic became popular with the release of NodeJS and many languages have tried to apply this feature. It is also one of the foremost concepts in server-side development that our engineers need to understand.

Please enjoy and provide feedback (to my email) if there are any mistakes in the post, thanks.

Asynchronous Programming

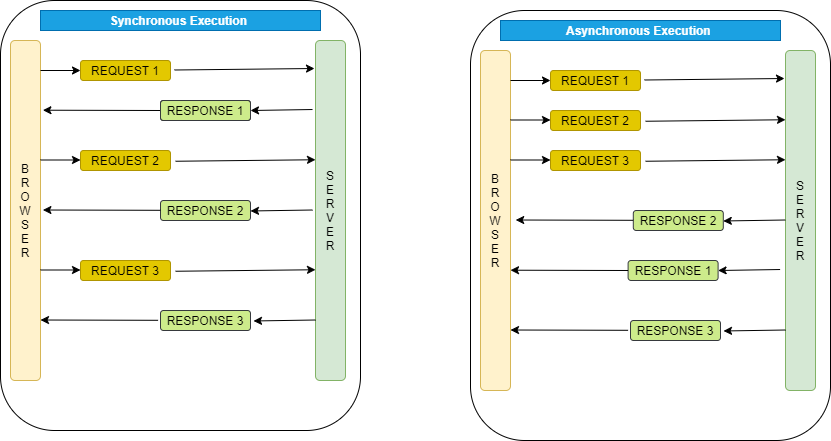

Before tackling this concept, we should have a solid understanding of synchronous programming. Synchronous programming is the traditional way in which instructions are executed, from top to bottom, and each instruction must be done before running the next.

For example, if we are building a crawler and it needs to crawl 3 sites, we need to execute 3 request calls sequentially like the code below:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

import requests

res = requests.get("https://site1.com")

print(f"Content of site 1: {res.content}")

res = requests.get("https://site2.com")

print(f"Content of site 2: {res.content}")

res = requests.get("https://site3.com")

print(f"Content of site 3: {res.content}")

By using synchronous programming, the third request only executes after the second request is done, and the second request only executes after the first request is done. Assuming each request takes 3 seconds to complete, the process runs in 9 seconds.

This whole process causes slowness because it depends on the third parties; if the third party is slower, the process will wait longer. It’s ideal if 3 requests could execute simultaneously and return the response at once because the requests don’t rely on each other. Here’s where asynchronous programming comes in handy.

Instead of waiting to return the response directly, asynchronous I/O delays the execution and returns a Future (Python)/Promise (JavaScript) as an execution proof without blocking the thread and continuing to invoke other requests. To be clear, asynchrony still goes through the instructions from top to bottom, it just delays the execution and returns another form of the result directly.

In the example, after sending all requests, these Futures will be constantly checked until the responses are available. As you can imagine, 3 crawling requests run simultaneously without waiting for one after another. So the whole process only takes around 3 seconds to complete, which is 3 times faster.

But does this sound familiar with threading? Don’t worry, we will go through how it runs and compare them in the next section.

Asynchronous Programming in Python

Python began supporting asynchronous programming a long time ago with gevent, in version 3.4 which first introduced the Asyncio package - the core for asynchronous programming - and version 3.5 introduced async/await keywords.

Note: Async I/O is different from the Asyncio package. The package supports running Async I/O in Python.

Async I/O is a single-threaded and single-process design. It uses cooperative multitasking to handle a large number of I/O operations like database queries and third-party requests. This design boosts the performance of handling I/O operations significantly, which is very relevant in this era where many computational-intensive tasks are handled by service providers effectively.

Coroutine/Future/Task

Async I/O begins with defining async functions. Each function defined with the async keyword is called a coroutine; when the coroutine executes, it returns a future representing the eventual result of an asynchronous operation.

Coroutines are a more generalized form of subroutines. Subroutines are entered at one point and exited at another point. Coroutines can be entered, exited, and resumed at many different points. — (Python Glossary)

This whole process is running in the Event Loop, which we will address later, where coroutines are executed using tasks. A Task, to be specific, is a sub-class of Future that runs a Python coroutine.

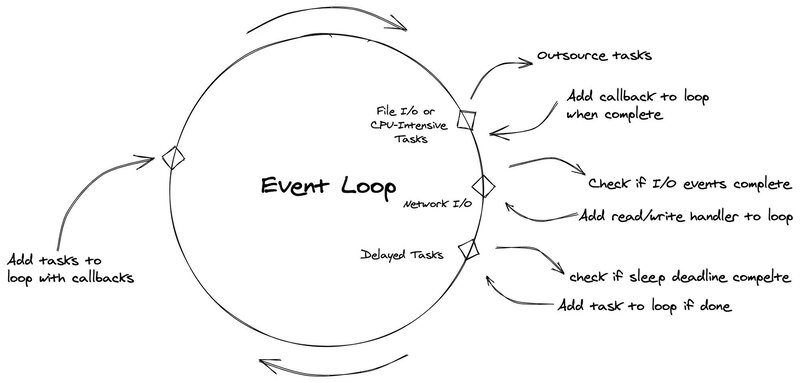

Asynchronous I/O Flow: When executing a long-running coroutine, Python first creates a task and runs the coroutine within the task in the context of the Event Loop. In the document of Python, it says: “If a coroutine awaits on a Future, the Task suspends the execution of the coroutine and waits for the completion of the Future. When the Future is done, the execution of the wrapped coroutine resumes (callback)” (“AsyncIO Task”, n.d.).

Event Loop

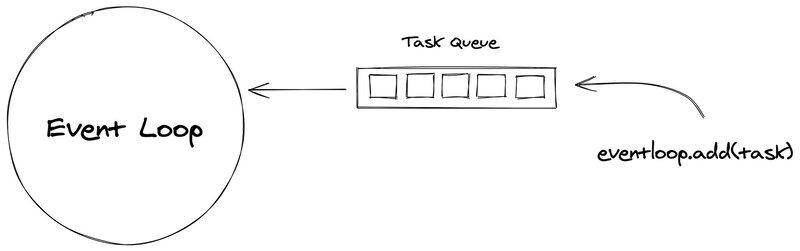

As I mentioned above, an Event Loop is where all of the work happens. It can also be called the core of asynchronous operations in every asynchronous platform.

When a Task is registered (executed), it will be put into a Task Queue, the loop will traverse through each item and execute them one at a time. While the Task awaits the completion of a Future (using await keyword), the loop runs other Tasks, callbacks, or performs I/O operations (“Coroutine and Tasks”).

Note: The Event Loop runs on the main thread and executes Tasks sequentially.

Questions:

- If the coroutine is CPU-bound and computationally expensive, will it block the Event Loop in Python?

⇒ Yes, it will block the Event Loop running in the main thread. If you define a coroutine and specify some heavy-lifting instructions, this means these instructions will run directly by the Event Loop. It will take time until other tasks get processed.

⇒ Blocking the Event Loop should be avoided because it hurts the performance and decreases the throughput of the system.

- Where should the CPU-intensive Tasks be handled?

⇒ It is recommended to run these Tasks in a ThreadPool or a ProcessPool instead of the main thread. This is better because ProcessPool has many workers which can use multiple CPU cores instead of one.

Asyncio package

Let’s test the Asyncio package a bit because this is the heart of asynchronous programming in Python.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

import asyncio

from asyncio import events

async def test():

print(123)

# check if a function is a coroutine

print(asyncio.iscoroutinefunction(test))

# run the coroutine. Behind the scene, it creates a new event loop,

# then wraps the coroutine with a task and executes it.

asyncio.run(test())

# asyncio.run behind the scene.

# 1. Create a new event loop

# 2. Run the coroutine

event_loop = events.new_event_loop()

event_loop.run_until_complete(test())

We can also run a coroutine in the background before actually awaiting it. Calling a coroutine alone is not enough because a warning is shown immediately RuntimeWarning: coroutine 'test' was never awaited. As you can see below, the Task is already finished even before awaiting it. It also doesn’t show any warning.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

import asyncio

async def test2():

print(123123)

async def test():

task = asyncio.create_task(test2())

await asyncio.sleep(10)

print(task)

await task

asyncio.run(test())

# 123123

# <Task finished name='Task-2' coro=<test2() done, defined at test_asyncio.py:6> result=None>

Demo the example above a little bit. There are two versions, the grequests package uses Gevent and the aiohttp package uses Asyncio (They are packages supporting asynchrony). I recommend using aiohttp to better adapt Python’s newer versions.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

import asyncio

import aiohttp

import grequests

import requests

import time

def run_synchronous_code():

start = time.time()

res = []

res1 = requests.get("http://httpbin.org/delay/3")

res.append(res1)

res2 = requests.get("http://httpbin.org/delay/3")

res.append(res2)

res3 = requests.get("http://httpbin.org/delay/3")

res.append(res3)

end_time = time.time() - start

print(res)

print("End:", end_time)

print("Average response time:", end_time / 3)

def run_asynchronous_code_gevent():

start = time.time()

urls = [

"http://httpbin.org/delay/3",

"http://httpbin.org/delay/3",

"http://httpbin.org/delay/3",

]

res = (grequests.get(url) for url in urls)

res = grequests.map(res)

end_time = time.time() - start

print("run_asynchronous_code_gevent")

print(res)

print("End:", end_time)

async def fetch(session, url):

async with session.get(url) as res:

return await res.json()

async def run_asynchronous_code_asyncio():

start = time.time()

urls = [

"http://httpbin.org/delay/3",

"http://httpbin.org/delay/3",

"http://httpbin.org/delay/3",

]

async with aiohttp.ClientSession() as session:

# run multiple requests simutaneously

res = await asyncio.gather(*[fetch(session, url) for url in urls], return_exceptions=True)

end_time = time.time() - start

print("run_asynchronous_code_asyncio")

# print(res)

print("End:", end_time)

return res

run_synchronous_code()

print()

run_asynchronous_code_gevent()

print()

asyncio.run(run_asynchronous_code_asyncio())

# run_synchronous_code

# [<Response [200]>, <Response [200]>, <Response [200]>]

# End: 11.448019981384277

# Average response time: 3.816006660461426

#

# run_asynchronous_code_gevent

# [<Response [200]>, <Response [200]>, <Response [200]>]

# End: 4.113437175750732

#

# run_asynchronous_code_asyncio

# End: 4.878862142562866

Comparison with other approaches

Comparison is the best way to understand which tool to use in which circumstances, so we will compare 3 concepts: Coroutines, Threads, and Processes.

| Coroutine | Thread | Process | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race conditions | Without context switches, it’s less likely to happen because the Event Loop is single-threaded and tasks are executed sequentially. But it still happens in some cases when memory is shared between coroutines. | Very likely to happen because context switches are mainly used to run threads concurrently. | Don’t happen because processes don’t use shared memory |

| Creation speed (1.000.000 items - code below) | Fastest (7s) | Slow (44s) | Slowest (379s) |

| Memory overhead (1.000.000 items) | 1112 MB | 2660 MB | Unable to calculate because processes use different memory spaces. |

| Ease of Use and Debug | Easy by having shared memory and just a few race conditions. | Hard because of using locking mechanisms to prevent unexpected cases. | Hard because of not having a shared memory. |

| Scheduling | By the application (manageable) | By the OS | By the OS |

| Computational capacity (CPU-intensive tasks) | Low-Medium because the Event Loop only uses 1 CPU | Low-Medium because of Global Interpreter Lock (can only execute one thread at a time using 1 CPU) | Medium-High because of using multiple CPUs |

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

# code for measuring time and memory usage

import multiprocessing

import threading

import asyncio

import psutil

import time

def test():

...

async def test2():

...

loop = asyncio.new_event_loop()

asyncio.set_event_loop(loop)

async def main():

mem_before = psutil.Process().memory_info().rss

start = time.time()

coroutines = []

for i in range(1000000):

coroutines.append(asyncio.create_task(test2()))

mem_after = psutil.Process().memory_info().rss

print("Async I/O time:", time.time() - start)

print("Memory consumption: %0.2fMB" % ((mem_after - mem_before) / 1024 / 1024))

loop.run_until_complete(main())

# Async I/O time: 6.777068614959717

# Memory consumption: 1111.67MB

mem_before = psutil.Process().memory_info().rss

threads = []

start = time.time()

for i in range(1000000):

thread = threading.Thread(target=test)

thread.start()

threads.append(thread)

print("Thread time:", time.time() - start)

mem_after = psutil.Process().memory_info().rss

print("Memory consumption: %0.2fMB" % ((mem_after - mem_before) / 1024 / 1024))

# Thread time: 43.58382987976074

# Memory consumption: 2660.73MB

start = time.time()

for i in range(1000):

process = multiprocessing.Process(target=test)

process.start()

print("Process time:", time.time() - start)

# Process time: 0.37912821769714355

# With 1.000.000 processes, it would take 379s.

As you can see, using asynchrony will benefit the system in multiple aspects, such as saving resources and increasing the system’s throughput. Besides, to me and other Python developers who have used synchronous programming for years, one disadvantage is the syntax; it’s quite challenging to use the asyncio library, but it’s an interesting process.

Conclusion

After the post, will you still stick with threads and processes or use coroutines? Personally, it depends on the situation that we face. If the task is computationally expensive, using coroutines is not the right approach.

Anyway, hope you enjoy this post, please don’t forget to send me feedback if anything in this content is incorrect or bugs you so much. I will try my best to write more blog posts like this in the future.

References

- Brownlee. J. (2022). Multiprocessing Race Conditions in Python. SuperFastPython. https://superfastpython.com/multiprocessing-race-condition-python

- Castelino. L. (2021). Build Your Own Event Loop from Scratch in Python. Medium. https://python.plainenglish.io/build-your-own-event-loop-from-scratch-in-python-da77ef1e3c39

- Coroutines and Tasks: https://docs.python.org/3/library/asyncio-task.html

- Don’t Block the Event Loop (or the Worker Pool): https://nodejs.org/en/docs/guides/dont-block-the-event-loop/

- Event Loop: https://docs.python.org/3/library/asyncio-eventloop.html

- Luminousmen. (n. d.) Asynchronous programming. Await the Future. https://luminousmen.com/post/asynchronous-programming-await-the-future