In the environments where I have worked, I personally think my colleagues’ mindsets and approaches to coding aren’t wise; they just follow their instinct without considering the refactoring factor. They always think code should not depend on any abstraction because abstraction is literally abstract (hard to understand and navigate in the editor). Those result in lengthy code (1-300 lines a function) which is impossible to maintain. I also see this from myself in the past, just getting the work done is good enough.

Unlike them and my old self, I like to add more abstraction to code to make it more maintainable, it also can be changed easily without impacting the old modules and logic. I have read quite a lot about design patterns to improve my coding skills. Gradually, they become my favorite tool and I try to apply them whenever I see appropriate. Today, I will show you how to use one of the behavioral patterns - Bridge.

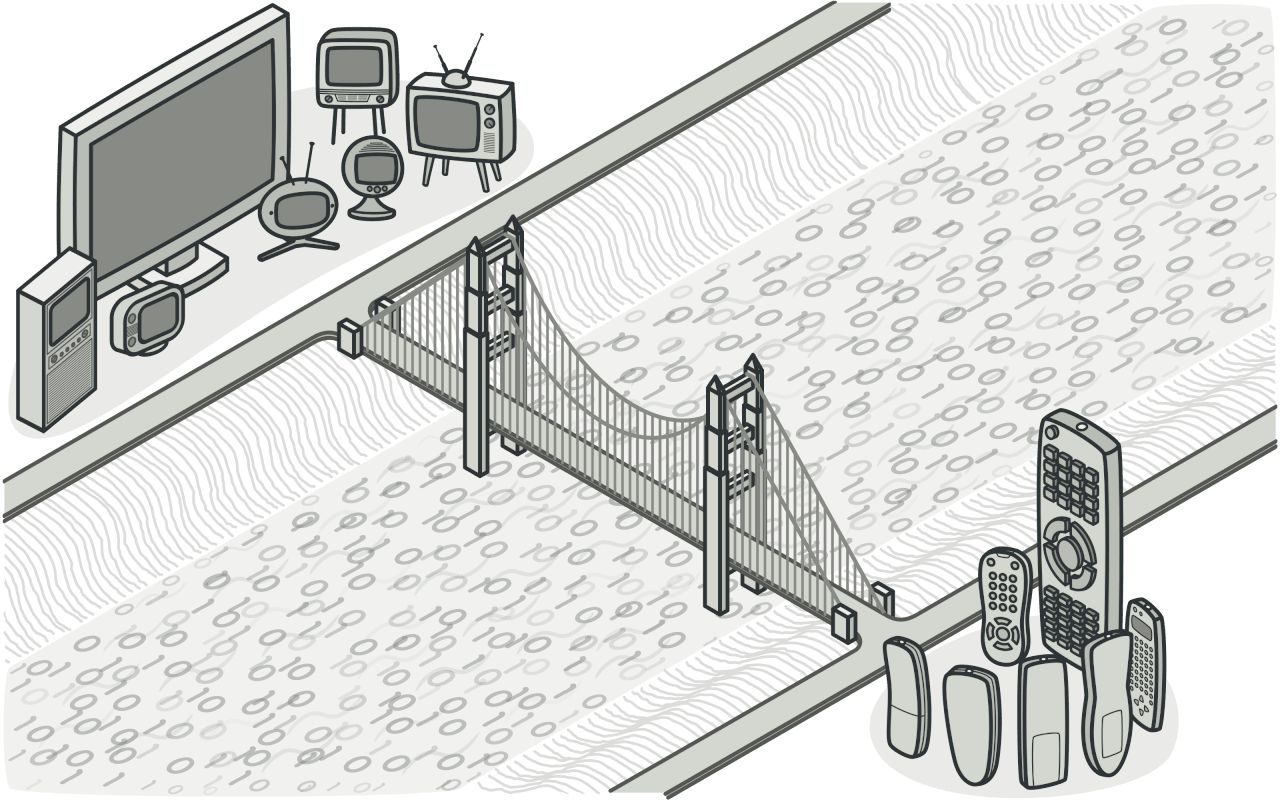

Retrieved from RefactoringGuru

Retrieved from RefactoringGuru

1. Definition

According to RefactoringGuru, “Bridge is a structural design pattern that lets you split a large class or a set of closely related classes into two separate hierarchies—abstraction and implementation—which can be developed independently of each other”.

Simply put, it helps us divide big classes into smaller ones but still remain the connectivity between these classes.

2. A Practical Example

The example I’m about to mention happens countless times in many source codes, maybe you’ll also find it similar to your source as well.

Example: Imagine you have a small crawler service that contains a few methods, let’s say 5 methods in the beginning. As time passes by, the application grows bigger and attracts more clients, they demand you to crawl more complicated sites. Therefore, the number of methods won’t stay still, it could possibly be 1-200 methods. So how can we avoid this situation? (In fact, when the service is added up more features and we don’t have a plan to refactor it, having a big fat class is just a matter of time).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

class CrawlingService:

def __init__(self):

...

def crawl_website_A(self):

...

def crawl_website_B(self):

...

def crawl_website_C(self):

...

def crawl_website_D(self):

...

def crawl_website_E(self):

...

def _crawl_by_http_request(self):

...

def _crawl_by_puppeteer(self):

...

First, we need to conduct some analysis to see if there is anything we can break down. In our case, we can see that the code crawls multiple websites using different methods. There are a few approaches here but it really depends on the content we crawl.

After finishing analyzing, we should refactor the code to make ourselves less guilty to developers who will maintain the source.

Approach 1: This approach is for websites having low-complexity accessing mechanisms (just by using trivial Puppeteer code or sending a simple HTTP request). Even though the majority of websites have different HTML structures, we can use unified code and receive these distinct structures as the parameters.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

import abc

class Website:

def __init__(

self,

url: str,

list_item: str,

item_title: str,

item_quantity: str,

item_description: str

):

...

class Engine(abc.ABC):

@abc.abstractmethod

def crawl(self, url: str) -> str:

...

class HttpRequestEngine(Engine):

def crawl(self, url: str) -> str:

print("Crawling using HTTP requests")

html = ""

return html

class PuppeteerEngine(Engine):

def crawl(self, url: str) -> str:

print("Crawling using Puppeteer")

html = ""

return html

class CrawlingService:

def __init__(self, website: Website, engine: Engine):

self._website = website

self._engine = engine

def crawl(self):

html = self._engine.crawl(self._website.url)

# use BeautifulSoup to parse HTML based on the structure defined in self._website

print("Parsing...")

def main():

website = Website("website-a.com", "div.main > div.list", ".title", ".quantity", ".description")

engine = PupeteerEngine()

crawling_service = CrawlingService(website, engine)

crawling_service.crawl()

The approach above I learned in a book named Web Scraping with Python, you can check my summary on this book here. This approach follows the composition characteristic, which is extremely easy to add new websites even though it is less recognizable compared to having multiple methods.

Approach 2: For modern websites that use front-end frameworks like Vue and React, it is difficult to retrieve the content. Besides, there are other elements like authentication and authorization that affect the crawling process. Therefore, the code above doesn’t fully solve the problem, it creates a dead-end instead. We need another approach that can customize for each specific case, this is when the Bridge pattern becomes handy.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

import abc

class Website:

def __init__(

self,

url: str,

list_item: str,

item_title: str,

item_quantity: str,

item_description: str

):

...

# Base class

class WebsiteCrawler(abc.ABC):

@abc.abstractmethod

def crawl(self, url: str):

...

class WebsiteACrawler(WebsiteCrawler):

def crawl(self, url: str):

print("Crawling using any particular engine")

print("Do authentication")

print("Do authorization")

print("Do other stuffs that the above code is not capable to do")

class CrawlingService:

def __init__(self, website: Website, crawler: WebsiteCrawler):

self._website = website

self._crawler = crawler

def crawl(self):

html = self._crawler.crawl(self._website.url)

# use BeautifulSoup to parse HTML based on the structure defined in self._website

print("Parsing...")

def main():

website = Website("website-a.com", "div.main > div.list", ".title", ".quantity", ".description")

crawler = WebsiteACrawler(website.url)

crawling_service = CrawlingService(website, crawler)

crawling_service.crawl()

To catch bigger fish, we need to use more advanced rods. This situation is the same, we need to use appropriate tools to solve bigger problems. Now, each website has its own unique class and this is what the Bridge Pattern aims to do. We still can utilize the first approach by implementing HttpRequestCrawler and PuppeteerCrawler like below:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

class HttpRequestCrawler(WebsiteCrawler):

def crawl(self, url: str) -> str:

print("Crawling using HTTP requests")

html = ""

return html

class PuppeteerCrawler(WebsiteCrawler):

def crawl(self, url: str) -> str:

print("Crawling using Puppeteer")

html = ""

return html

3. Conclusion

Now, do you see how great it is to use the Bridge pattern? By using it, we will less likely to have a big fat class in the future when our applications scale into a bigger size. Even though we cannot recognize this pattern by instinct, we should try to understand the code, detect the pattern within, and refactor.

Hope you enjoy this one, I will continue writing about some useful patterns in the later articles.

4. References

- RefactoringGuru. (n. d.). Bridge. Retrieved from https://refactoring.guru/design-patterns/bridge.