I have just finished the book Web Scraping with Python yesterday, it’s a useful book that helps you improve your scraping skills. There is some useful information there, you should take a look before deciding to work on any scraping projects. Below are the things that are helpful in my future scraping projects.

1. Try-except is a savior

Imagine you are crawling a big site with 100.000 data items, it takes you a few days to complete. If any exception happens (resource not found, the server is down), it will disrupt the whole process and you have to run over again.

Therefore, in my opinion, try-except and exception handlers are extremely important during any long scraping process.

2. Dealing with placeholder images

Most websites rendering images often use the blank images or base64 content as a placeholder to prevent layout reflow, where the content below or around the image gets pushed to make room for the freshly loaded image. Therefore, we have to ignore them completely and aim for the original links.

Thankfully, the book uses BeautifulSoup, it is a strong library that is based on top of the parsers (HTML, XML, …) to extract the content. The library below supports Regex to selectively choose the appropriate content. We can write some patterns to skip the base64 content and the blank images.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

# the code here is retrieved from Web Scraping with Python

import re

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

res = requests.get('http://www.pythonscraping.com/pages/page3.html')

html = res.content.decode('utf-8')

bs = BeautifulSoup(html, 'html.parser')

# ignore placeholder images

images = bs.find_all('img', {'src':re.compile('\.\.\/img\/gifts/img.*\.jpg')})

for image in images:

print(image['src'])

3. Crawl an entire website

In the past, I wondered how to write a scraper to crawl the entire website. Fortunately, I have found the secret ingredient here, the whole process only contains 3 steps:

- Crawl any pages any page on the website

- Parse and get all internal links

- Recursively do the first and second steps

Note: We need to maintain a links list that was already crawled to avoid infinite recursion.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

# the code here is retrieved from Web Scraping with Python

from urllib.request import urlopen

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

import re

pages = set()

def getLinks(pageUrl):

global pages

html = urlopen('http://en.wikipedia.org{}'.format(pageUrl))

bs = BeautifulSoup(html, 'html.parser')

try:

print(bs.h1.get_text())

print(bs.find(id ='mw-content-text').find_all('p')[0])

print(bs.find(id='ca-edit').find('span').find('a').attrs['href'])

except AttributeError:

print('This page is missing something! Continuing.')

for link in bs.find_all('a', href=re.compile('^(/wiki/)')):

if 'href' in link.attrs:

if link.attrs['href'] not in pages:

#We have encountered a new page

newPage = link.attrs['href']

print('-'*20)

print(newPage)

pages.add(newPage)

getLinks(newPage)

getLinks('')

4. Dealing with Different Website Layouts

When crawling specific content (such as blog articles, news, and mangas) from multiple websites, it’s important to have a consistent class blueprint whose each property describes the DOM path of an element in the content. With the same code, we can crawl thousands of websites’ layouts with little effort.

For example, the code below crawls the title and content of 4 articles on 4 different websites. If it was me in the past, I would create 4 different functions to handle the tasks.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

# the code here is retrieved from Web Scraping with Python

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

class Crawler:

def getPage(self, URL):

try:

req = requests.get(url)

except requests.exceptions.RequestException:

return None

return BeautifulSoup(req.text, 'html.parser')

def safeGet(self, pageObj, selector):

"""

Utility function used to get a content string from a

Beautiful Soup object and a selector. Returns an empty

string if no object is found for the given selector

"""

selectedElems = pageObj.select(selector)

if selectedElems is not None and len(selectedElems) > 0:

return '\n'.join([elem.get_text() for elem in selectedElems])

return ''

def parse(self, site, url):

"""

Extract content from a given page URL

"""

bs = self.getPage(url)

if bs is not None:

title = self.safeGet(bs, site.titleTag)

body = self.safeGet(bs, site.bodyTag)

if title != '' and body != '':

content = Content(url, title, body)

content.print()

class Content:

"""

Common base class for all articles/pages

"""

def __init__(self, url, title, body):

self.url = url

self.title = title

self.body = body

def print(self):

"""

Flexible printing function controls the output

"""

print("URL: {}".format(self.url))

print("TITLE: {}".format(self.title))

print("BODY:\n{}".format(self.body))

class Website:

"""

Contains information about website structure

"""

def __init__(self, name, url, titleTag, bodyTag):

self.name = name

self.url = url

self.titleTag = titleTag

self.bodyTag = bodyTag

crawler = Crawler()

siteData = [

['O\'Reilly Media', 'http://oreilly.com', 'h1', 'section#product-description'],

['Reuters', 'http://reuters.com', 'h1', 'div.StandardArticleBody_body_1gnLA'],

['Brookings', 'http://www.brookings.edu', 'h1', 'div.post-body'],

['New York Times', 'http://nytimes.com', 'h1', 'p.story-content']

]

websites = []

for row in siteData:

websites.append(Website(row[0], row[1], row[2], row[3]))

crawler.parse(websites[0], 'http://shop.oreilly.com/product/0636920028154.do')

crawler.parse(websites[1], 'http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-epa-pruitt-idUSKBN19W2D0')

crawler.parse(websites[2], 'https://www.brookings.edu/blog/techtank/2016/03/01/idea-to-retire-old-methods-of-policy-education/')

crawler.parse(websites[3], 'https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/28/business/energy-environment/oil-boom.html')

From the code above, siteData can be retrieved from a database or even a CSV file.

5. Text Encoding

Three main encoding formats:

- ASCII

- UTF-8, UTF-16, UTF-32

- ISO-8859

According to the author, there are 9% of websites use ISO encoding. We can use this tag <meta charset="utf-8" /> to determine the encoding, hence using the appropriate decoding method.

You should also note that when reading any kind of content, taking up hard drive space with files when you could easily keep them in memory is bad practice.

6. Submit Form

Submit form is simple as calling API, but how to break through the CSRF wall is still a mystery to me. 😭

1

2

3

4

5

import requests

params = {'email_addr': 'myemail@gmail.com'}

r = requests.post("[http://post.oreilly.com/client/o/oreilly/forms/quicksignup.cgi](http://post.oreilly.com/client/o/oreilly/forms/quicksignup.cgi)", data=params)

print(r.text)

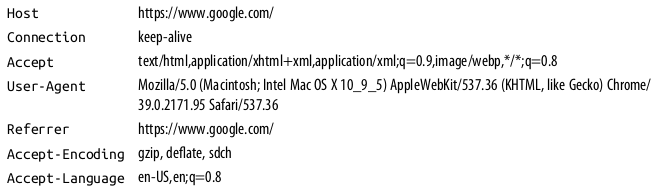

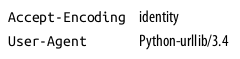

7. Looking Like a Human

When we crawl, remember to make your requests’ headers like the browsers, we can override them with the requests package in Python. This makes our requests more natural and it’s harder to differentiate between humans and crawlers.

Major browsers’ header:

Default urllib library’s header:

Besides, we should avoid modifying hidden input fields as well as honeypots, they are the common security features to double-check the crawlers. On top of that, timing is also a critical thing because a single user cannot send hundreds of requests a second.

8. Summary

Even though there are more things that should be discussed like Scrapy and Puppeteer, I think they would deserve their own posts due to the immense complexity. That is all for now, thanks for reading.

9. References

- Mitchell. R. (2018). Web Scraping with Python (2nd Edition). O’Reilly